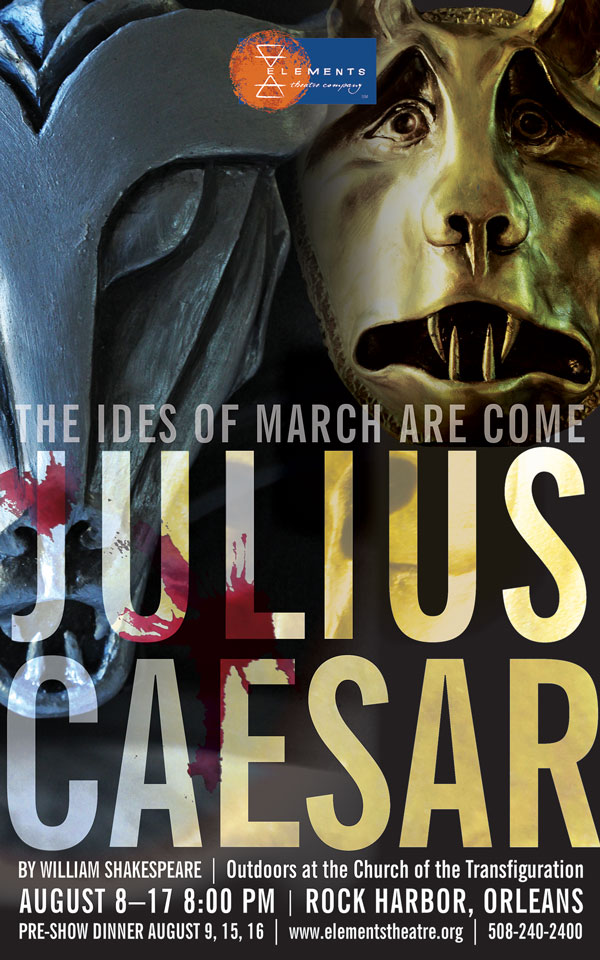

Show Information

From the Director

Show Gallery

From the Director

Dear Friends,

Julius Caesar is rife with the violence of betrayal. The phrase, Et tu Brute, has taken on new weight for me in this rehearsal process. I have repeatedly watched Caesar turned on by a wolf pack of conspirators and blindsided as he reaches toward his one hope, Brutus. Betrayal is always personal. Like violence.

Brutus, torn by conflict and reason, can only hope that his choice to murder Caesar is the best for the Rome he sees in decay. It is a quandary in this play—who are the real aggressors?

Brutus and Cassius, who move out in anticipation of what Caesar might do, based on his recent actions and the people’s fervor for him?

Or Caesar, who crossed the Rubicon defying Roman law, declared himself a God, and became dictator of Rome?

Caesar is viciously struck down (historically 33 stab wounds) by people he knows and some he loves. Brutus and Cassius, who are at the center of this, are run out of the city they thought they were saving and eventually die violently. For their betrayal, the poet, Dante, places the two of them in the lowest circle of Hell with Judas. Which was a probable influence on Shakespeare since his education was in the shadow of the middle ages.

In the myth of Romulus and Remus, Rome was founded on betrayal and fratricide. How like Cain and Able, and the first betrayal in the Garden of Eden. Centuries have past and yet we struggle with the same natures and look for relief from those faults that plague us.

“Men at some times are masters of their fates.

The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars,

But in ourselves…”

—Act 1, scene 2

Stories can be a relief from and an answer to these faults, if we wish. It seems for Shakespeare that was part of his purpose in writing them.

All the Best,